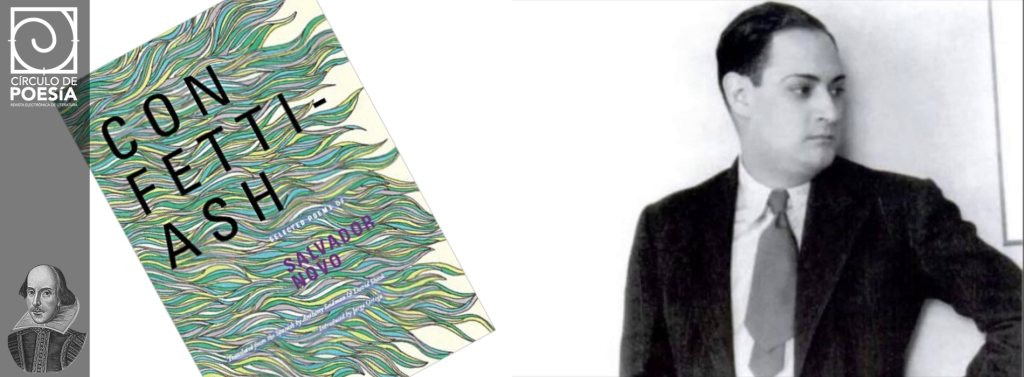

Today at Círculo de Poesía: Selected Poems of Salvador Novo (1904-1974). A poet who changes the direction of Mexican poetry based on aesthetic approach, Pedro Henriquez Ureña took from American Poetry, “write like you talk”. The present selection comes from that anthology, compiled and translated by californian poet Anthony Seidman and David Shook, with an introductory essay by mexican poet Jorge Ortega. [CONFETTI-ASH: Selected Poems of Salvador Novo, 2015]

Presentamos una selección del poeta mexicano Salvador Novo (1904-1974), traducida por el poeta californiano Anthony Seidman. Los poemas pertenecen a la antología CONFETTI-ASH: Selected Poems of Salvador Novo, compilada y traducida por Seidman y David Shook, con un ensayo introductorio de Jorge Ortega, para la editorial neoyorkina SPD. Salvador Novo modificó la dicción de la poesía mexicana al actualizar la máxima estética que trajo Pedro Henríquez Ureña de Estados Unidos: “escribir como se habla”.

Epifania

One Sunday

Epifania didn’t return home.

I eavesdropped as they spoke

of some man who had taken her;

later, by pestering the maids,

I learned that he had brought her to a room.

I never found out where this room was located,

but I imagined it: cold, unfurnished,

with a floor of clayish earth,

and a single door opening to the street.

When I thought of that room,

I couldn’t see anyone there.

Epifania returned one evening,

and I chased her throughout the garden,

begging for her to tell me what the man had done to her,

because my room was empty

like a box containing no surprise.

Epifania would laugh and run off,

then finally opened the door

and made it so that the street enter the garden.

Epifania

Un domingo

Epifania no volvió más a la casa.

Yo sorprendí conversaciones

en que contaban que un hombre se la había robado

y luego, interrogando a las criadas,

averigüé que se la había llevado a un cuarto.

No supe nunca dónde estaba ese cuarto

pero lo imaginé, frío, sin muebles,

con el piso de tierra húmeda

y una sola puerta a la calle.

Cuando yo pensaba en ese cuarto

no veía a nadie en él.

Epifania volvió una tarde

y yo la perseguí por el jardín

rogándole que me dijera qué le había hecho el hombre

porque mi cuarto estaba vació

como una caja sin sorpresas.

Epifania reía y corría

y al fin abrió la puerta

y dejó que la calle entrara en el jardín.

The Friend Who Left

Napoleon writes to me, saying:

“The school is very big,

we get up very early,

we only speak in English,

here’s a drawing of the building…”

No longer will we steal candy

from the cupboard, nor escape

to the river in order to nearly drown

or pick bloody watermelons.

This year I start sixth grade;

later, according to the general statistics,

I’ll learn the rigmarole:

I’ll be a doctor;

ambitious, I’ll sport a beard and slacks…

But if I have a son

I’ll make sure no one teaches him anything.

I want him to stay lazy, happy,–

the opposite of how I was reared by my parents,

my parents by my grandparents,

my grandparents by God.

El Amigo Ido

Me escribe Napoleón:

“El Colegio es muy grande,

nos levantamos muy temprano,

hablamos únicamente en inglés,

te mando un retrato del edificio…”

Ya no robaremos juntos dulces

de las alacenas, ni escaparemos

hacia el río para ahogarnos a medias

y pescar sandías sangrientas.

Ya voy a presentar sexto año;

después, según las probabilidades,

aprenderé todo lo que se deba,

seré médico,

tendré ambiciones, barba, pantalón largo…

Pero si tengo un hijo

haré que nadie nunca le enseñe nada.

Quiero que sea tan perezoso y feliz

como a mí no me dejaron mis padres

ni a mis padres mis abuelos

ni a mis abuelos Dios.

Almanac

I

We have twelve spots

to spend the seasons:

summer can be spent in June,

Fall must be spent in October.

Time guides us

through its houses of four floors

with seven rooms, living room, two bedrooms,

dining room, patio, kitchen

and bathroom.

Each day closes a door

we will never see again,

then opens another window of surprise.

A gust knocked down

two rooms from the topmost floor

of February.

The wind dies down,

and we continue searching for a roof.

II

The scythe of the minute-hand

established its very center

in the center of our belly.

For the mailboxes of life

we required rubber stamps stating: Certified.

Address your mail to street and number.

And we´re here already, the last available post-office,

without finding the paperknife of a smile

in either December or March.

Our navels

will be peeled off by stamp-collectors!

Wrinkled, covered with scars,

and stuffed with old news,

we’ll be returned to sender….

Almanaque

I

Tenemos doce lugares

para pasar las estaciones:

el verano se puede pasar en Junio

el Otoño se debe pasar en Octubre.

El tiempo nos conduce

por sus casa de cuatro pisos

con siete piezas. Sala, dos recámaras,

comedor, patio, cocina

y cuarto de baño.

Cada día Cierra una puerta

que no voldremos a ver

y abre otra sorpredente ventana.

El aire derribó

dos cuartos del último piso

de Febrero.

El aire se serena

y seguimos buscando casa.

II

La guadaña del minutero

hizo centro de su compás

en el centro de nuestro vientre.

Para los buzones de la vida

necesitábamos certificado.

Address your mail to street and number.

Y estamos en la poste restante

sin hallar en diciembre ni en marzo

la plegadera de una sonrisa.

¡Nuestro ombligo

va a ser para los filatelistas!

y seremos devuletos al remitente

Ajados, con cicatrices

y llenos de noticias atrasadas…

School

At fixed hours

they wake us up, comb our hair and send us off to school.

The boys swarm on the playground, make

a ruckus and knock each other down;

then a bell rings,

and we march to the classrooms quietly.

We sit with a partner at our desks,

and with pencils sharpened to different lengths,

we write down what the teacher dictates,

or go up to the chalkboard.

The teacher doesn’t like me;

he glares at my expensive clothes

and my brand-new books.

He doesn’t know that I’d give all of that to the other boys

if only I could play like they do,

without this queer shyness that makes me feel so inferior,

when I flee from them during recess,

or when upon leaving school,

I run home,

run home to my mother.

La escuela

A horas exactas

nos levantan, nos peinan, nos mandan a la escuela.

Vienen los muchachos de todas partes,

gritan y se atropellan en el patio

y luego suena una campana

y desfilamos, callados, hacia los salones.

Cada dos tienen un lugar

y con lápices de todos tamaños

escribimos lo que nos dicta el profesor

o pasamos al pizarrón.

El profesor no me quiere;

ve con malos ojos mi ropa fina

y que tengo todos los libros.

No sabe que se los daría todos a los muchachos

por jugar con ellos, sin este

pudor extraño que me hace sentir tan inferior

cuando a la hora del recreo les huyo,

cuando corro, al salir de la escuela,

hacia mi casa, hacia mi madre.

History

Death to the gachupines!

My father is a gachupín,

the teacher looks at me with hate

and recounts the War of Independence

and how the Spanish were evil and cruel

with the Indians—he is an Indian—

and all the boys yell, Death to the gachupines.

But I rebel

and think they’re very stupid:

That is what history says

but how are we to know?

La historia

¡Mueran los gachupines!

Mi padre es gachupín,

el profesor me mira con odio

y nos cuenta la Guerra de Independencia

y cómo los españoles eran malos y crueles

con los indios —él es indio—,

y todos los muchachos gritan que mueran

los gachupines

Pero yo me rebelo

y pienso que son muy estúpidos:

Eso dice la historia

pero ¿cómo lo vamos a saber nosotros?

Impossible Renovation

Everything, poet, everything—the book,

that coffin—straight into the wastebasket!

Words as well, those

dictators!

You’re well aware of what neither

the word nor the coffin convey.

The moon, the star, the flower,

straight into the wastebasket! Using two fingers,

pick up the heart! Nowadays,

everyone has one…

and then the hyperbolic mirror,

and the eyes; everything, poet,

straight into the wastebasket!

And yet, the wastebasket?…

La Renovación Imposible

Todo, poeta, todo—el libro,

ese ataúd–¡al cesto!

y las palabras, esas

dictadoras.

Tú sabes lo que no consigan

la palabra ni el ataúd.

La luna, la Estrella, la flor

¡al cesto! Con dos dedos…

¡El corazón! Hoy todo el mundo

lo tiene…

Y luego el espejo hiperbólico

y los ojos, ¡todo poeta!

¡al cesto!

Mas ¿el cesto…?

My Life Is Like A Lake

My life is like a taciturn lake.

If a distant cloud greets me,

if there’s bird chirping, if a mute

and hidden breeze

burns the essence of the roses,

if there’s a blood-colored blush

during the vague, twilight hour,

I wince and offer my smile.

My life is like a taciturn lake!

I’ve learnt how to form, drop

by drop, my blue depths

where I behold the universe.

Each new stirring gave me its tone,

each diverse matrix

gave me its rhythm, taught me its verse.

My life is a like a taciturn lake….

Mi Vida Es Como Un Lago

Mi vida es como un lago taciturno.

Si una nube lejana me saluda,

si hay un ave que canta, si una muda

y recóndita brisa

inmola el desaliento de las rosas,

si hay un rubor de sangre en la imprecisa

hora crepuscular,

yo me conturbo y tiendo mi sonrisa.

¡Mi vida es como un lago taciturno!

Yo he sabido formar, gota por gota,

mi fondo azul de ver el Universo.

Cada nuevo rumor me dio su nota,

cada matiz diverso

me dio su ritmo y me enseñó su verso.

Mi vida es como un lago taciturno….

First Grey Hair

Sudden, first

grey

hair, like an icy hello

from the one I love most…

you gave me the slip, and among

this riot of hair I haven’t found you again;

now I look for you,

as one indifferently seeks

a forgotten face.

I needn’t hide you;

the whole world could pass by,

it would be absurd for anyone

to suspect your presence.

Only I will know about this buried treasure.

I’ll scribble some humorous lines,

and you’ll forget me while I greet

people; if the barber uncovers you,

he will scientifically

expound on your presence,

then prescribe a hair tonic.

He’ll be the only one to know about you

but I’ll hush him in disbelief,

ask him to be discrete,

and you’ll remain one fleeting

thought amid a myriad.

In twenty years, you will long

have gone off into the world;

by then it will be normal

for no one to spot you

among others of the same age.

Primera cana

Primera cana

Súbita

has sido como un saludo frío

de la que se ama más.

Pronto te me perdiste en el tumulto

no te he vuelto a encontrar,

pero te busco

indiferentemente

como se busca la casualidad.

No he de ocultarte a nadie

todo el mundo pasará junto a mí

sin sospecharte, absurda.

Sólo yo he de saber de ese tesoro.

Ahora escribiré algunas cosas humoristas;

te me olvidarás en tanto

saludo a numerosas personas

y si el peluquero te descubre

me explicará científicamente tu presencia

y me recetará una loción.

Será el único que te sepa

pero lo callará por discreto y descreído

y serás así en mí como un pensamiento

en medio de numerosa concurrencia.

Dentro de veinte años

te habrás perdido por el mundo

pero entonces ya será natural

que no se te encuentre

a la edad adecuada, entre las otras.

The Cities

In Mexico, in Chihuahua,

in Jimenez, in Parral, in Madera,

in Torren,

the frozen winters and the clear mornings,

the people’s houses,

the big buildings where nobody lives

or the theaters where they go and sit

or the churches where they kneel

and the animals that have grown used to people

and the river that runs by the church

and that grows turbulent with last night’s rain

or the swamp where the frogs grow up

and the garden where the wildflowers open

each afternoon, at five o’clock, near the kiosk

and the market full of vegetables and baskets

and the rhythm of the days and Sunday

and the station where the train

that each day deposits and takes away new people

on the beads of its rosary

and the faint-hearted night

and Saint Lucia’s eyes

in the shade’s parasol

and always the family

and the father that works and returns

and dinner time and the friends

and the families and the visitors

and the new suit

and the letters from another city

and the swallows level with the ground

or on their stone balcony beneath the roof.

And everywhere

like a drop of water

mixing with the sand that receives it.

Las ciudades

En México, en Chihuahua.

en Jiménez, en Parral, en Madera,

en Torreón,

los inviernos helados y las mañanas claras,

las casas de la gente,

los grandes edificios en que no vive nadie

o los teatros a los que acuden y se sientan

o la iglesia donde se arrodillan

y los animales que se han habituado a la gente

y el río que pasa cerca del pueblo

y que se vuelve turbulento con la lluvia de anoche

o el pantano en que se crían las ranas

y el jardín en que se abren las maravillas

todas las tardes, a las cinco, cerca del quiosco

y el mercado lleno de legumbres y cestas

y el ritmo de los días y el domingo

y la estación del ferrocarril

que a diario deposita y arranca gentes nuevas

en las cuentas de su rosario

y la noche medrosa

y los ojos de Santa Lucía

en el quitasol de la sombra

y la familia siempre

y el padre que trabaja y regresa

y la hora de comer y los amigos

y las familias y las visitas

y el traje nuevo

y las cartas de otra ciudad

y las golondrinas al ras del suelo

o en su balcón de piedra bajo el techo.

Y en todas partes

como una gota de agua

mezclarse con la arena que la acoge.

Geography

With these color blocks

I can build an altar and a house

and a tower and a tunnel,

and then I can knock them down.

But at school

they’ll want me to draft a map with a pencil,

they’ll want me to draw the world,

and the world scares me.

God created the world,

I can only

build an altar and a house.

La Geografía

Con estos cubos de colores

yo puedo construir un altar y una casa,

y una torre y un túnel,

y puedo luego derribarlos.

Pero en la escuela

querrán que yo haga un mapa con un lápiz,

querrán que yo trace el mundo

y el mundo me da miedo.

Dios creó el mundo

yo solo puedo

construir un altar y una casa.

Summaries

I

My books

have in them the seasons

when I read them,

La Légende des siècles, three weeks

in bed, fruit salts and thermometers.

For vacation in the countryside

—never eclogues or georgics—

Sherlock Holmes and Rollinat

and in the doctor’s waiting room

Monsieur Bergeret à Paris.

And I hate to read them, because I believe

in the resurrection of the flesh.

Nathanael, Nathanael,

Harald Höffding

is guilty of these things!

When we resurrect

—I plan to do so—

between us and our century

there will be an association of ideas

despite our condition.

II

From my corner

now that I have turned my face

I see three angles.

Childlike problem

Divine Providence

each cat sees three cats

which are actually—when seen properly—

four match tips in summary.

A son, a book, a tree

and a single true heart.

Long ago I was young

and I did not know the Rule of Three.

Resúmenes

I

Mis libros

tienen en sí las épocas

en que los leí.

Le Légende des siècles, tres semanas

en cama, sal de frutas y termómetros.

Para las vacaciones en el campo

—nunca églogas ni geórgicas—

Sherlock Holmes y Rollinat

y en las antesalas del medico

Monsieur Bergeret à Paris.

Y odio abrirlos, porque creo

en la resurreción de la carne.

¡Nathanael, Nathanael,

Harald Höffding

tiene la culpa de estas cosas!

Cuando resurrezcamos

—yo tengo pensado hacerlo—

entre nosotros y este siglo

habrá una asociación de ideas

a pesar de nuestro formato.

II

Desde mi rincón

ahora que volteado la cara

veo tres ángulos.

Infantil problema

Divina Providencia

cada gato vet res gatos

y no son sino, bien visto,

cuatro puntos de fódforo en resumen.

Un hijo, un libro, un árbol

y un solo corazón verdadero.

Antaño yo era joven

y no sabía la regla de tres.

The City

We arrived by walking through this great door;

I was scared of those harried men at the station,

each one offered to lend a hand,

and the cars frightened me too…

I would get lost here, alone,

among so many smooth, long streets;

nobody knows who I am,

the lights are more blinding,

the windows taller, and locked…

La Ciudad

Por esta puerta grande hemos llegado,

yo les temía a esos hombres rápidos de la estación,

todos ellos se ofrecen para algo

y los automóviles…

Yo me perdería aquí, solo,

en tanta calle lisa y larga;

ninguna persona sabe quién soy,

las luces son más Fuertes,

las ventanas más altas y cerradas…

Poetry

To write poems,

to be a poet of the passionate, romantic life,

(one whose books are clutched by everyone’s hands,

one who appears in newspaper photos and is the subject of books),

it’s necessary to tell you what I read,

things about the heart, women, and the landscape,

lovesickness, a life that’s painful, meted out

in perfect meter, no cacophony in the lines,

with new, sparkling metaphors.

The music of verse is like liquor,

and if one knows how to allude pointedly to one’s inspiration,

he will jerk tears from those in the auditorium,

he will reveal his hidden sentiments,

and he will be laureled in ceremonies and contests.

I can craft perfect verses,

measure them, avoid cacophony,

poems that move those who read them,

then exclaim: What a smart boy!

I will tell them

that I’ve been writing since I was eleven:

I won’t ever tell them

That I haven’t done anything but teach them what

I have learned from all of the poets.

I’ll have knack for playacting, for getting them to

believe that I am moved by what moves them.

But in my lonely bed, sweetly,

with no memories, with no voice,

I feel poetry hasn’t chosen me.

La poesía

Para escribir poemas,

para ser un poeta de vida apasionada y romántica

cuyos libros están en las manos de todos

y de quien hacen libros y publican retratos

los periódicos,

es necesario decir las cosas que leo,

esas del corazón, de la mujer y del paisaje,

del amor fracasado y de la vida dolorosa,

en versos perfectamente medidos,

sin asonancias en el mismo verso,

con metáforas nuevas y brillantes.

La música del verso embriaga

y si uno sabe referir rotundamente su inspiración

arrancará las lágrimas del auditorio,

le comunicará sus emociones recónditas

y será coronado en certámenes y concursos.

Yo puedo hacer versos perfectos,

medirlos y evitar sus asonancias,

poemas que conmuevan a quien los lea

y que les hagan exclamar: “¡Qué niño tan inteligente!”

Yo les diré entonces

que los he escrito desde que tenía once años:

No he de decirles nunca

que no he hecho sino darles la clase que he aprendido de todos los poetas.

Tendré una habilidad de histrión

para hacerles creer que me conmueve lo que a ellos.

Pero en mi lecho, solo, dulcemente,

sin recuerdos, sin voz,

siento que la poesía no ha salido de mí.

Night

Laborer:

it’s not that I’m a socialist;

but you have spent the entire day

caring for a machine

invented by Americans

to meet needs

invented by Americans.

I have heard

facts that don’t concern me

and which, at learning them, would make me

comprehensive, social, explicit,

and a Doctor of Philosophy,

I have my brain or whatever it is

full of skull-moths.

Now both of us have inhaled

the black cantharides of silence.

The circulation of the hours

has culminated in a whirlwind

and we have become impermeable.

Down different paths

we both knock on the same door.

Three automobiles wait on three generals

the mist of a player piano

splashes our head,

trunk and extremities,

That girl’s not wearing stockings!

That Lady Windermere

considers the boundaries

of your feet and your hands

for a longitudinal sorites.

Your bride and mine

will make laces and projects.

Everyone is asleep, but

Voici ma douce amie

si méprisée ici car elle est sage

and numerical and temperamental.

Farewell, friend, good luck

with Lady Gordiva. [sic]

For me, Vive la France

although my friend

cannot now, materially,

enjoy le compliment.

Noche

Obrero:

no es que yo sea socialista;

pero tú has pasado el día entero

cuidadno una máquina

inventada por americanos

para cubrir necesidades

inventadas por americanos.

Yo he oído

datos que no me conciernen

y que, de aprender, me harían

comprensivo, social, explícito

y Doctor en Filosofía.

Tengo el cerebro o lo que sea

lleno de polilla de cráneos.

Ahora ambos aspirado

la cantárida negra del silencio.

La circulación de las horas

ha culminado en tromba

y nos hemos puesto impermeables.

Por diversos caminos

los dos llamamos a la misma puerta.

Tres autos esperan a tres generals

un vaho de pianola

nos salpica cabeza,

tronco y extremidades.

¡Esa chica no trae medias!

Aquella Lady Windermere

medita las premisas

de tus pies y tus manos

para un sorites longitudinal.

Tu novia y la mía

harán encajes y proyectos.

Todos duermen, pero

Voici ma douce amie

si méprisée ici car ell est sage

and numerical and tempermental.

Adiós, amigo, éxito

con Lady Gordiva.

Por mí, Vive la France

aunque mi amiga

no pueda ahora, materialimente,

agradecer el compliment.

Flood

The ballroom was spacious,

soul and mind comprised

two full orchestras;

a costume party where

words entered, and vowels

offered their arms to consonants.

Maidens, escorted by knights,

wore raiments

from the Medieval period or

antiquity; there were

cuneiform tablets,

papyrus, stone etchings,

gamma, delta, omicron,

peploses, gowns, togas, suits of armor,

and barbarian fur atop

rugged, hairy chests;

and the long, purple cloak of Lent,

and the hellish color of Dante’s hood,

and the alfalfa fields of Castilian,

with the wigs of many blond Juliets,

and the heads of John the Baptists

and Marie Antoinettes

who lacked both heart and womb,

and Prince Charming

dressed in threads of wind,

and a monosyllabic princess

who was certainly no Madam Butterfly,

and a black courtier,

elastic and rubbery,

with teeth white as inlays of marble.

They all danced within me,

holding cold hands;

with ancient, evaporated perfume,

they wore diverse costumes,

from distinct epochs and

speaking different tongues.

Inconsolable, I wept!

Though all the lifetimes

from all the points,

whirled to the dance of the ages,

that masque was so sad!

So I set my heart on fire,

and the feathery tufts

of vowels and consonants crackled,

and it was a pity to see

the rubies adorning the Grand Vizier’s turban

thunder like chestnuts,

along with the finery from Watteau

and the consorts with towering

coiffures who would gather

in Queen Victoria’s chamber.

I should also say

that all of the nuns,

(both from before and after Christ),

were consumed by flames,

and that many heroes

stoically awaited their deaths,

while others swallowed their poisoned rings.

The blaze lasted for long,

and in the end I only saw

the confetti-ash in my heart

which I removed and

discovered therein a nameless child,

naked, completely naked,

with no age, mute, eternal,

and, Oh!, never, ever will the child learn that grapevines

and apples have gone to California,

nor that locomotives exist.

My ballroom has closed for good;

my heart no longer has the music of all the beaches,

from now on it will possess the silence of all the centuries.

Diluvio

Espaciosa sala de baile

alma y cerebro

dos orquestas, dos,

baile de trajes,

las palabras iban entrando,

las vocales daban el brazo a las consonantes.

Señoritas acompañadas de caballeros

y tenían trajes de la Edad Media

y de muchísimo antes

y ladrillos cuneiformes

papiros, tablas,

gama, delta, ómicron,

peplos, vestes, togas, armaduras,

y las pieles bárbaras sobre las pieles ásperas

y el gran manto morado de la cuaresma

y el color de infierno de la vestidura de Dante

y todo el alfalfar Castellano,

las pelucas de muchas Julietas rubias

las cabezas de Iokanaanes y Marías Antonietas

sin corazón ni vientre

y el Príncipe Esplendor

vestido con briznas de brisa

y una princesa monosilábica

que no era ciertamente Madame Butterfly

y un negro elástico de goma

con ojos blancos como incrustaciones de marfil.

Danzaban todos en mí

cogidos de las manos frías

en un antiguo perfume apagado

tenían todos trajes diversos

y distintas fechas

y hablaban lenguas diferentes.

Y yo lloré inconsolablemente

porque en mi gran sala de baile

estaban todas las vidas

de todos los rumbos

bailando la danza de todos los siglos

y era, sin embargo, tan triste

esta mascarada!

Entonces prendí fuego a mi corazón

y las vocales y las consonantes

flamearon un segundo su penacho

y era lástima ver el turbante del gran Visir

tronar los rubíes como castañas

y aquellos preciosos trajes Watteau

y todo el estrado Queen Victoria

de damas con altos peinados.

También debo decir

que se incendiaron todas las monjas

B.C. y C.O.D.

y que muchos héroes esperaron

estoicamente la muerte

y otros bebían sus sortijas envenenadas.

Y duró mucho el incendio

mas vi al fin en mi corazón únicamente

el confeti de todas las cenizas

y al removerlo

encontré

una criatura sin nombre

enteramente, enteramente desnuda,

sin edad, muda, eterna,

y ¡oh! nunca, nunca sabrá que existen las parras

y las manzanas se han trasladado a California

y ella no sabrá nunca que hay trenes!

Se ha clausurado mi sala de baile

mi corazón no tiene ya la música de todas

las playas

de hoy más tendrá el silencio de todos los siglos.