Aquí la sexta entrega del Premio Pulitzer de Poesía que contiene una selección de poemas del libro ganador de este certamen, seleccionados y traducidos por David Ruano González y nuestra editora, Andrea Muriel. Se trata de una muestra representativa del trabajo de cada uno de los poetas que han ganado este galardón, uno de los más importantes en lengua inglesa, haciendo un recorrido cronológico de 1990 hasta nuestros días.

.

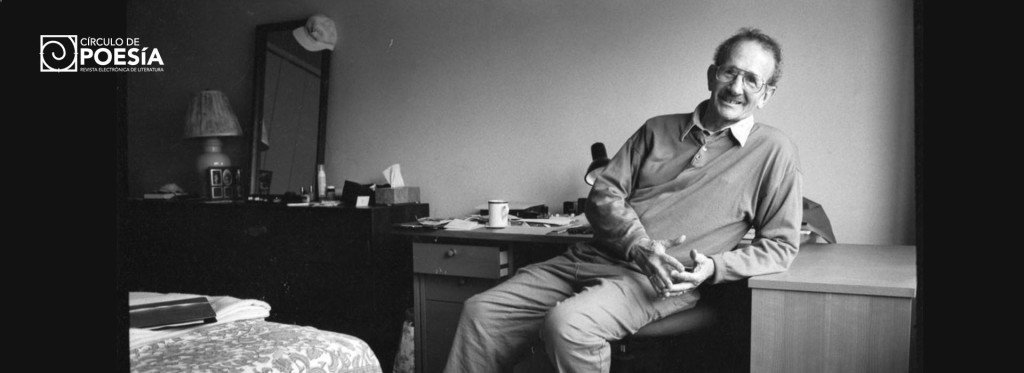

En esta ocasión presentamos una selección de poesía de Philip Levine (Detroit, Michigan, 1928 – Fresno, California, 2015) que recibió el Premio Pulitzer de Poesía en 1995 con el libro The Simple Truth. Una de las más grandes virtudes de este libro se encuentra en el descubrimiento de elementos cotidianos desde una sencillez deslumbrante. El jurado que le otorgó el Pulitzer es también de mencionarse: Louise Glück, Mark Strand y Charles Wright. Levine también obtuvo el National Book Award algunos años antes, en 1991, con What Work Is y en 2011 fue Poeta Laureado de los Estados Unidos.

Para ver las entregas pasadas, haz click aquí.

.

.

.

UN DÍA

Todos saben que los árboles se irán un día

y nada tomará su lugar.

Todos se han despertado, solos, en

un cuarto de luz fresca y han subido

a conocer la mañana como nosotros lo hicimos.

Qué tanto hemos esperado

silenciosamente a un lado del camino

para que alguien lento se detenga y preguntar por qué.

La luz se está yendo, primero de entre

las largas filas de oscuros abetos

y después de nuestros ojos, y cuando

ya se ha ido nosotros nos habremos ido.

Nadie quedará para decir,

“Él tomó la rama y marcó

el lugar donde la puerta debería estar”

o “ella sujetó al niño con ambas manos

y cantó la misma canción

una y otra vez.”

Antes de la cena nos formábamos

en línea para lavarnos la grasa de nuestras caras

y restregarnos las manos con un cepillo duro,

y el recipiente del agua espesado y grisáceo,

con una suciedad blanca hecha espuma en la cima,

y el último arrojaba el agua al patio.

Papas hervidas, con mantequilla y sal, cebollas,

gruesas rebanadas de pan, leche fría

casi azul debajo de la luz débil,

el olor del café proveniente de la cocina.

Sentía mis ojos cerrarse lentamente.

Tú fumabas en silencio.

¿Qué vida

estábamos esperando? Barcos partieron

de puertos distantes sin nosotros,

el teléfono sonó y nadie contestó,

alguien vino a casa solo y se quedó

por horas en el oscuro vestíbulo.

Una mujer se inclinó a una vela

y le habló como si ésta la pudiera oír,

como si le pudiera responder.

Mi tía fue a la ventana trasera

y llamó a su hijo menor, que desde hace

27 años está bajo la custodia

del estado, diciendo su nombre una

y otra vez. ¿Qué podía yo hacer?

¿Responder por él, pues se había olvidado

de su nombre? ¿Tomar los zapatos de mi padre

e ir a buscarlo a las calles?

Sí, el sol

ha salido de nuevo. Puedo ver las ventanas

nuevas y escuchar a un perro ladrar. El viento

cede a la delgada cima del aliso,

la conversación de las aves nocturnas

se calla, y puedo escuchar mi corazón

fuerte y regular. Viviré para ver

el final de día así como viví para ver

la tierra volverse líquida y blanca,

luego en metal, luego en cualquier estado

que acuñamos ahí mientras reímos

por largas horas de la noche o cantamos

cómo el águila vuela los viernes.

Cuando llegó el viernes, las tempranas horas perfectas

y frías, maldijimos nuestras propias vidas

y pasamos la botella de atrás para delante.

Algunos murieron.

Yo volví y él se fue, mi amigo

con la gran sonrisa, que caminaba

cautelosamente y comía con la cabeza

baja, como un oso, y su áspero cabello

casi tocaba el plato. Aquel alto

con brazos no tan gruesos como los de una chica,

quien maldijo su cara deforme

como si pudiera tener otra.

Aquel cuya voz se entonaba suavemente

cuando levantaba un dedo y hablaba. Me senté

a su lado, tratando de describir el mar

como si lo hubiera visto, pero el mar estaba perdido,

distante e invisible, tal vez ya no

se encontraba bajo el cielo próximo. Traté de decirle

cómo las olas se oscurecieron y dejaron solamente

el sonido de su romper,

y después un silencio que aprendimos a soportar,

todo regresó. Él se dio vuelta

hacia la pared y se durmió, y yo me fui

a la ciudad. Fui yo quien sostuvo a su esposa

y sintió los huesos pequeños de su espalda

levantándose y cayéndose como si ella no llorara.

Después vi a mi hijo a una distancia

y no lo llamé. Pude levantarme esa noche

a lado de una mujer que dormía y contar

cada respiro.

De pronto ya era verano, en la tarde,

la ciudad se escondía dentro del gran calor,

el aire caliente secaba nuestras caras. Yo dije

“ellos se fueron”. La luz cambió de rojo

a verde y avanzamos. “Si ellos no están aquí”,

dijiste, “¿dónde están?” Nos quedamos

mirando el cielo como si

ese fuera nuestro único hogar. Manejamos.

Nada removido, nada revuelto

en el horno de este valle. ¿Qué

quedaba por decir? El cielo

estaba en llamas, el aire entraba

por las ventanas abiertas. Nos liberamos

más allá de los lotes de autos, las ventanas pintadas,

los bares de toda la noche, los lugares

donde los niños se reunían, y nosotros sólo

nos pasamos de largo, tan lejos como podíamos

en un día que nunca terminó.

Traducción por David Ruano González

.

.

.

.

EL POEMA DEL GIS

De camino al bajo Broadway

me encontré esta mañana con un hombre alto

hablando con un pedazo de gis

que sostenía en su mano derecha. La izquierda

se encontraba abierta, y mantenía el pulso

ya que su charla tenía un ritmo,

que era un canto o una danza, quizá

incluso un poema en francés, dado que él

era de Senegal y hablaba francés

tan despacio y de un modo tan preciso que yo

podía entenderlo como si

hubiera regresado en el tiempo cincuenta años a mi

salón de clases de la preparatoria. Un hombre esbelto,

elegante a su modo, vestido impecablemente

en los restos de dos trajes azules,

la corbata anudada de modo cuadrado, su camisa blanca

sin manchas aunque sin planchar. Él sabía

la entera historia del gis, no sólo

la de este pedazo en particular, sino también

la del gis con el que yo escribí

mi nombre el día en que me dieron la bienvenida

de vuelta en la escuela después de la muerte

de mi padre. Él conocía el feldespato,

conocía el calcio, conchas de ostras, él

sabía que las criaturas habían dado

sus espinas para volverse el polvo del tiempo

presionado en estos perfectos conos,

él conocía la tristeza en los salones de clases

en diciembre cuando se oscurece

temprano y las palabras en el pizarrón

abandonan su gramática y sentido,

y luego incluso su forma para que

cada letra señale a todas direcciones

al mismo tiempo y no signifique absolutamente nada.

Al principio pensé que su corta barba

estaba escarchada con gis pero cuando estuvimos

cara a cara a no más de 30 centímetros

uno del otro, vi que las barbas eran blancas,

ya que aunque joven, en sus gestos

él era, como yo, un hombre envejecido, aunque

mucho más noble en apariencia con sus altas

mejillas esculpidas, los hombros amplios

y sus transparentes ojos oscuros. Él tenía el porte

de un rey del bajo Broadway, alguien

salido de la mente de Shakespeare o

García Lorca, alguien para el cual la pérdida

se había endulzado en caridad. Permanecimos ahí

por un largo minuto, ambos

compartiendo el último poema de gis

mientras la gran ciudad bramaba alrededor

de nosotros, y luego el poema terminaba, como todos

los poemas lo hacen, y su mano izquierda se dejó caer

abruptamente a su lado para entregarme

el pedazo de gis. Yo hice una reverencia,

sabiendo lo enorme que era este regalo

y escribí mi agradecimiento en el aire

donde podrá escucharse para siempre

debajo del grito endurecido de una concha de mar.

Traducción por Andrea Muriel

.

.

.

.

SOÑANDO EN SUECO

La nieve cae sobre los altos juncos pálidos

cerca de la costa, e incluso aunque en algunos lugares

el cielo es pesado y oscuro, un pálido sol

se asoma a través de ellos y arroja su luz amarilla

en la cara de las olas que llegan.

Alguien dejó una bicicleta recargada

contra el retoño de un árbol joven y se adentró

en el bosque. Los rastros de un hombre

desaparecieron entre los pesados pinos y robles,

un hombre lento, con pie grande, arrastra

su pie derecho en un ángulo extraño

mientras intenta llegar a la única casita de campo blanca

que lanza su pluma de humo hacia el cielo.

Él debe ser el cartero. Una bolsa de tela,

medio cerrada, se sienta en una caja de madera

sobre la llanta de adelante. Los discretos

cristales de nieve se filtran uno a uno

borrando la dirección de una sola carta,

aquella que escribí en California y envié

sabiendo que no llegaría a tiempo.

¿Qué tiene que ver con nosotros esta costa

cerca de Malmö, y la blanca casita de campo

sellada herméticamente contra el viento, y la nieve

cayendo todo el día sin sentido

o necesidad? Ahí está nuestra bolsa de tela de las preguntas,

si tan sólo pudiéramos encontrar las cartas para cada una.

Traducción por Andrea Muriel

.

.

.

.

LA SIMPLE VERDAD

Compré dólar y medio de pequeñas papas rojas,

las llevé a casa, las puse a hervir en su cáscara

y me las comí en la cena con un poco de mantequilla y sal.

Luego caminé por los campos secos

a las orillas del pueblo. A mediados de junio la luz

colgaba de los oscuros surcos a mis pies,

y en los robles de la parte alta de las montañas los pájaros

se reunían por la noche, los cuervos y los ruiseñores

graznaban por todos lados, los pinzones aún se movían rápidamente

por la luz polvorienta. La mujer que me vendió

las papas era de Polonia; ella era una persona

que surgía de mi infancia con un suéter de lentejuelas rosas y unos lentes de sol

alabando la perfección de todas sus frutas y verduras

desde su puesto de carretera y me insistía en probar

incluso las pálidas, fresco maíz dulce transportado en camiones,

juraba ella, desde Nueva Jersey. “Come, come,” decía,

“Incluso si no lo haces diré que lo hiciste”.

Algunas cosas

las sabes toda tu vida. Son tan simples y verdaderas

que deben ser dichas sin elegancia, metro o rima,

deben ser puestas en la mesa junto al salero,

al vaso de agua, a la ausencia de luz captada

en las sombras de los portarretratos, deben estar

desnudas y solas, deben sostenerse por sí mismas.

Mi amigo Henri y yo llegamos juntos a esto en 1965

antes de que yo me fuera lejos, antes de que él empezara a matarse a sí mismo,

y los dos traicionáramos nuestro cariño. ¿Puedes saborear

lo que te estoy diciendo? Son cebollas o papas, una pizca

de simple sal, la riqueza de la mantequilla derritiéndose, es obvio,

permanece en tu garganta como una verdad

que nunca dirás porque el tiempo siempre es el equivocado,

permanecerá ahí por el resto de tu vida, sin decirse,

fabricada de esa suciedad que llamamos tierra, el metal que llamamos sal,

en una forma para la que no tenemos palabras, y tú vives en ello.

Traducción por David Ruano González

.

.

.

.

ONE DAY

Everyone knows that the trees will go one day

and nothing will take their place.

Everyone has wakened, alone,

in a room of fresh light and risen

to meet the morning as we did.

How long have we waited

quietly by the side of the road

for someone to slow and ask why.

The light is going, first from between

the long rows of dark firs

and then from our eyes, and when

it is gone we will be gone.

No one will be left to say,

“He took the stick and marked off

the place where the door would be,”

or “she held the child in both hands

and sang the same few tunes

over and over.”

Before dinner we stood

in line to wash the grease from our faces

and scrub our hands with a hard brush,

and the pan of water thickened and grayed,

a white scum frothed on top,

and the last one flung it in the yard.

Boiled potatoes, buttered and salted, onions,

thick slices of bread, cold milk

almost blue under the fading light,

the smell of coffee from the kitchen.

I felt my eyes slowly closing.

You smoked in silence.

What life

were we expecting? Ships sailed

from distant harbors without us,

the telephone rang and no one answered,

someone came home alone and stood

for hours in the dark hallway.

A woman bowed to a candle

and spoke as though it could hear,

as though it could answer.

My aunt went to the back window

and called her small son, gone now

27 years into the closed wards

of the state, called his name again

and again. What could I do?

Answer for him who’d forgotten

his name Take my father’s shoes

and go into de streets?

Yes, the sun

has risen again. I can see the windows

change and hear a dog barking. The wind

buckles the slender top pf the alder,

the conversation of night birds

hushes, and I can hear my heart

regular and strong. I will live to see

the day end as I lived to see

the earth turn molten and white,

the to metal, then to whatever shape

we stamped into it as we laughed

the long night hours ways or sang

how the eagles flies on Friday.

When Friday came, the early hour perfect

and cold, we cursed our only lives

and passed the bottle back and forth.

Some died.

I turned and he was gone, my friend

with the great laugh who walked

cautiously and ate with his head

down, like a bear, his coarse hair

almost touching the plate. The tall one

with arms no thicker than girl’s,

who cursed his swollen face

as though he could have another.

The one whose voice lilted softly

when he raised a finger and spoke. I sat

beside him, trying to describe the sea

as I had seen it, but it was lost,

distant and unseen, perhaps no longer

there under a low sky. I tried to tell him

how the waves darkened and left only

the sound of the breaking,

and after a silence we learned to bear,

it all came back. He turned away

to the wall and slept, and I went out

into the city. It was I who’d held his wife

and felt the small bones of her back

rising and falling as she did not cry.

Later I would see my son from a distance

and not call out. I would waken that night

beside a sleeping woman and count

each breath.

Soon it was summer, afternoon,

the city hid indoors in the great heat,

the hot wind shriveled our faces. I said,

“They’re gone.” The light turned from red

To green, and we went on. “If they’re not here,”

you said, “where are they?” We both

looked into the sky as though

it were our only home. We drove on.

Nothing moved, nothing stirred

in the oven of this valley. What

was there left to say? The sky

was on fire, the air streamed

into the open windows. We broke free

beyond the car lots, the painted windows,

the all-night bars, the places

where the children gathered, and we just

went on and on, as far we could

into a day that never ended.

.

.

.

.

THE POEM OF CHALK

On the way to lower Broadway

this morning I faced a tall man

speaking to a piece of chalk

held in his right hand. The left

was open, and it kept the beat,

for his speech had a rhythm,

was a chant or dance, perhaps

even a poem in French, for he

was from Senegal and spoke French

so slowly and precisely that I

could understand as though

hurled back fifty years to my

high school classroom. A slender man,

elegant in his manner, neatly dressed

in the remnants of two blue suits,

his tie fixed squarely, his white shirt

spotless though unironed. He knew

the whole history of chalk, not only

of this particular piece, but also

the chalk with which I wrote

my name the day they welcomed

me back to school after the death

of my father. He knew feldspar.

he knew calcium, oyster shells, he

knew what creatures had given

their spines to become the dust time

pressed into these perfect cones,

he knew the sadness of classrooms

in December when the light fails

early and the words on the blackboard

abandon their grammar and sense

and then even their shapes so that

each letter points in every direction

at once and means nothing at all.

At first I thought his short beard

was frosted with chalk; as we stood

face to face, no more than a foot

apart, I saw the hairs were white,

for though youthful in his gestures

he was, like me, an aging man, though

far nobler in appearance with his high

carved cheekbones, his broad shoulders,

and clear dark eyes. He had the bearing

of a king of lower Broadway, someone

out of the mind of Shakespeare or

Garcia Lorca, someone for whom loss

had sweetened into charity. We stood

for that one long minute, the two

of us sharing the final poem of chalk

while the great city raged around

us, and then the poem ended, as all

poems do, and his left hand dropped

to his side abruptly and he handed

me the piece of chalk. I bowed,

knowing how large a gift this was

and wrote my thanks on the air

where it might be heard forever

below the sea shell’s stiffening cry.

.

.

.

.

DREAMING IN SWEDISH

The snow is falling on the tall pale reeds

near the seashore, and even though in places

the sky is heavy and dark, a pale sun

peeps through casting its yellow light

across the face of the waves coming in.

Someone has left a bicycle leaning

against the trunk of a sapling and gone

into the woods. The tracks of a man

disappear among the heavy pines and oaks,

a large-footed, slow man dragging

his right foot at an odd angle

as he makes for the one white cottage

that sends its plume of smoke skyward.

He must be the mailman. A canvas bag,

half-closed, sits upright in a wooden box

over the front wheel. The discrete

crystals of snow seep in one at a time

blurring the address of a single letter,

the one I wrote in California and mailed

though I knew it would never arrive on time.

What does this seashore near Malmo

have to do with us, and the white cottage

sealed up against the wind, and the snow

coming down all day without purpose

or need? There is our canvas sack of answers,

if only we could fit the letters to each other.

.

.

.

.

THE SIMPLE TRUTH

I bought a dollar and a half’s worth of small red potatoes,

took them home, boiled them in their jackets

and ate them for dinner with a little butter and salt.

Then I walked through the dried fields

on the edge of town. In middle June the light

hung on in the dark furrows at my feet,

and in the mountain oaks overhead the birds

were gathering for the night, the jays and mockers

squawking back and forth, the finches still darting

into the dusty light. The woman who sold me

the potatoes was from Poland; she was someone

out of my childhood in a pink spangled sweater and sunglasses

praising the perfection of all her fruits and vegetables

at the road-side stand and urging me to taste

even the pale, raw sweet corn trucked all the way,

she swore, from New Jersey. “Eat, eat” she said,

“Even if you don’t I’ll say you did.”

Some things

you know all your life. They are so simple and true

they must be said without elegance, meter and rhyme,

they must be laid on the table beside the salt shaker,

the glass of water, the absence of light gathering

in the shadows of picture frames, they must be

naked and alone, they must stand for themselves.

My friend Henri and I arrived at this together in 1965

before I went away, before he began to kill himself,

and the two of us to betray our love. Can you taste

what I’m saying? It is onions or potatoes, a pinch

of simple salt, the wealth of melting butter, it is obvious,

it stays in the back of your throat like a truthPhi

you never uttered because the time was always wrong,

it stays there for the rest of your life, unspoken,

made of that dirt we call earth, the metal we call salt,

in a form we have no words for, and you live on it.