Comenzamos la muestra del Premio Pulitzer de Poesía que contendrá una selección de poemas del libro ganador de este certamen, seleccionados y traducidos por David Ruano González y nuestra editora, Andrea Muriel. Se trata de una muestra representativa del trabajo de cada uno de los poetas que han ganado este galardón, uno de los más importantes en lengua inglesa, haciendo un recorrido cronológico de 1990 hasta nuestros días.

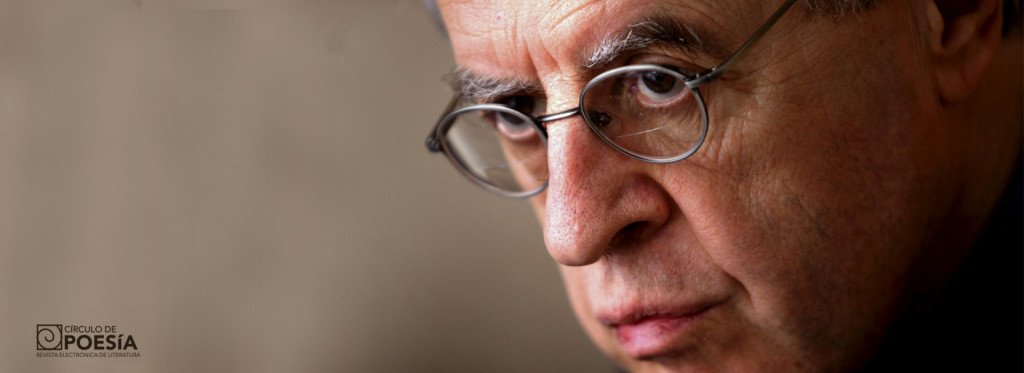

El dossier comienza con el ganador de 1990, Charles Simic (Belgrado, 1938), con The world doesn’t end, único libro de poemas en prosa que ha ganado el Premio Pulitzer.

Para ver todas las entregas, haz click aquí.

.

.

.

.

El mundo no se acaba

Parte I

.

Éramos tan pobres que tuve que sustituir la carnada en la ratonera. Completamente solo en el sótano, podía oírlos ir de un lado a otro en el piso de arriba, lanzándose y dando vueltas en sus camas. “Estos son días oscuros y malignos”, me dijo el ratón como si mordiera mi oreja. Los años pasaron. Mi madre vestía un cuello de pelo de gato que acarició hasta sacar chispas que iluminaron el sótano.

.

.

.

Todas las moscas del Círculo Ártico vienen de mis noches de insomnio. Así es como viajan: El viento las lleva de carnicero en carnicero; luego los rabos de las vacas se encuentran ocupados a la hora en que las ordeñan.

En la noche, en los bosques del norte, escuchan al alce, al león… Ahí los veranos son tan cortos que apenas tienen tiempo de contarse las patas.

“Tan valiente como una estampilla postal cruzando el océano”, zumban y suspiran, y ahora ya es tiempo de hacer bolas de nieve, de las pequeñas y grises con piedras dentro.

.

.

Parte II

.

Un poema sobre sentarse en una azotea de Nueva York en una fría tarde de otoño, bebiendo vino tinto, rodeado de altos edificios, niños pequeños corriendo peligrosamente hacia el borde, la bella chica de quien todos están secretamente enamorados sentada a solas. Ella morirá joven pero todavía no lo sabemos. Ella tiene un agujero en su media negra, mostrando su dedo grande, con la uña pintada de rojo… Y los rascacielos… a la luz menguante… como nuevos Caldeos, pitonisas, Casandras… por sus demasiadas ventanas ciegas.

.

.

.

Querido Friedrich, el mundo sigue siendo falso, cruel y hermoso…

Antes de que anocheciera, vi al chino de la tintorería, que no lee ni escribe en nuestra lengua, hojeando un libro que dejó algún cliente por las prisas. Eso me hizo feliz. Me hubiera gustado que fuera un libro de sueños, o un libro de versos estúpidamente sentimentales, pero no lo vi de cerca.

Ahora es casi medianoche, y todavía tiene las luces encendidas. Tiene una hija que le trae la cena, viste faldas cortas y camina con pasos largos. Está retrasada, demasiado, así que él ha dejado de planchar y se pone a mirar la calle.

Si no fuera por nosotros dos, ahí sólo habría arañas tejiendo sus redes entre las luces de la calle y los árboles oscuros.

.

.

Traducciones por David Ruano González

.

.

.

El hombre muerto se baja del cadalso. Sostiene su cabeza ensangrentada debajo del brazo.

Los manzanos están floridos. Él se dirige a la taberna del pueblo mientras todos lo miran. Ahí, toma un asiento en una de las mesas y ordena dos cervezas, una para él y otra para su cabeza. Mi madre se limpia las manos en su delantal y lo atiende.

Hay tanta quietud en el mundo. Uno puede escuchar el viejo río, que en su confusión algunas veces olvida y fluye hacia atrás.

.

.

.

Mi ángel de la guarda le tiene miedo a la oscuridad. Él pretende que no, me dice que me adelante y que se reunirá conmigo en cualquier momento. Muy pronto ya no puedo ver nada. “Éste debe de ser el rincón más oscuro del paraíso,” alguien suspira a mis espaldas. Resulta que su ángel de la guarda también ha desaparecido. “Esto es una atrocidad,” le digo. “Esos pequeños cobardes nos abandonaron,” ella murmura. Y por supuesto, por lo que sabemos, yo ya debo de tener alrededor de cien años y ella es sólo una adormilada niña con lentes.

.

.

.

Alguna vez lo supe, luego lo olvidé. Fue como si me hubiera quedado dormido en un campo sólo para descubrir al despertar que un bosque había crecido alrededor de mí.

“No dudes de nada, cree en todo,” era la idea de metafísica que tenía mi amigo, aunque su hermano se fugó con su esposa. Él aún le compraba una rosa cada día y se sentó en la casa vacía por los siguientes veinte años hablándole del tiempo.

Yo ya estaba cabeceando en las sombras, soñando que los crujidos de los árboles eran mis muchos yos explicándose todos al mismo tiempo para que yo no pudiera entender una sola palabra. Mi vida era un hermoso misterio al borde del entendimiento, ¡siempre al borde! ¡Piénsalo!

La casa vacía de mi amigo con todas sus ventanas iluminadas. Los oscuros árboles multiplicándose a su alrededor.

.

.

Parte III

.

El tiempo de los poetas menores se acerca. Adios Whitman, Dickinson, Frost. Bienvenidos ustedes cuya fama nunca llegará más allá de su familia más cercana y tal vez uno o dos buenos amigos reunidos después de la cena alrededor de una jarra de feroz vino tinto… mientras los niños mueren de sueño y se quejan por el ruido que estás haciendo mientras hurgas en los closets buscando tus viejos poemas, temeroso de que tu esposa los pueda haber tirado con la última limpieza de primavera.

Está nevando, dice alguien que ha echado un vistazo a la oscura noche, y entonces también él se voltea hacia ti mientras te preparas para leer, de un modo un tanto melodramático y poniéndote rojo de la cara, el largo y divagante poema de amor cuya estrofa final (desconocida para ti) se encuentra irremediablemente ausente.

A la manera de Aleksandar Ristović

.

.

.

Oh el Gran Dios de la Teoría, es sólo una punta de lápiz, una punta mordisqueada con su desgastada goma al final de un enorme garabato.

.

.

Traducciones por Andrea Muriel

.

.

.

The world doesn’t end

Part I

.

We were so poor I had to take the place of the bait in the mousetrap. All alone in the cellar, I could hear them pacing upstairs, tossing and turning in their beds. “These are dark and evil days,” the mouse told me as he nibbled my ear. Years passed. My mother wore a cat-fur collar which she stroked until its sparks lit up the cellar.

.

.

.

The flies in the Arctic Circle all come from my sleepless nights. This is how they travel: The wind takes them from butcher to butcher; then the cows’ tails get busy at milking time.

At night in the northern woods they listen to the moose, the lion… The summer there is so brief, they barely have time to count their legs.

“Brave as a postage stamp crossing the ocean,” they drone and sigh, and already it’s time to make snowballs, the little gray ones with stones in them.

.

.

Part II

.

A poem about sitting on a New York rooftop on a chill autumn evening, drinking red wine, surrounded by tall buildings, the little kids running dangerously to the edge, the beautiful girl everyone’s secretly in love with sitting by herself. She will die young but we don’t know that yet. She has a hole in her black stocking, big toe showing, toe painted red…And the skyscrapers… in the failing light… like new Chaldeans, pythonesses, Cassandras…because of their many blind windows.

.

.

.

Dear Friedrich, the world’s still false, cruel and beautiful…

Earlier tonight, I watched the Chinese laundryman, who doesn´t read or write our language, turn the pages of a book left behind by a costumer in a hurry. That made me happy. I wanted it to be a dreambook, or a volume of foolishly sentimental verses, but I didn’t look closely.

It’s almost midnight now, and his light is still on. He has a daughter who brings him dinner, who wears short skirts and walk with long strides. She’s late, very late, so he has stopped ironing and watches the street.

If not for the two of us, there’d be only spiders hanging their webs between the street lights and the dark trees.

.

.

.

The dead man steps down from the scaffold. He holds his bloody head under his arm.

The apple trees are in flower. He’s making his way to the village tavern with everybody watching. There, he takes a seat at one of the tables and orders two beers, one for him and one for his head. My mother wipes her hands on her apron and serves him.

It’s so quiet in the world. One can hear the old river, which in its confusion forgets and flows backwards.

.

.

.

My guardian angel is afraid of the dark. He pretends he’s not, sends me ahead, tells me he’ll be along in a moment. Pretty soon I can’t see a thing. “This must be the darkest corner of heaven,’ someone whispers behind my back. It turns out her guardian angel is missing too. “It’s an outrage,” I tell her. “The dirty little cowards leaving us alone,” she whispers. And of course, for all we know, I might be a hundred years old already, and she’s just a sleepy little girl with glasses.

.

.

.

Once I knew, then I forgot. It was as if I had fallen asleep in a field only to discover at waking that a grove of trees had grown up around me.

“Doubt nothing, believe everything,” was my friends idea of metaphysics, although his brother ran away with his wife. He still bought her a rose every day, sat in the empty house for the next twenty years talking to her about the weather.

I was already dozing off in the shade, dreaming that the rustling trees were my many selves explaining themselves all at the same time so that I could not make out a single word. My life was a beautiful mystery on the verge of understanding, always on the verge! Think of it!

My friend’s empty house with every one of its windows lit. The dark trees multiplying all around it.

.

.

Part III

.

The time of minor poets is coming. Good-by Whitman, Dickinson, Frost. Welcome you whose fame will never reach beyond your closest family, and perhaps one or two good friends gathered after dinner over a jug of fierce red wine… while the children are falling asleep and complaining about the noise you’re making as you rummage through the closets for your old poems, afraid your wife might’ve thrown them out with last spring’s cleaning.

It’s snowing, says someone who has peeked into the dark night, and then he, too, turns toward you as you prepare yourself to read, in a manner somewhat theatrical and with a face turning red, the long rambling love poem whose final stanza (unknown to you) is hopelessly missing.

After Aleksandar Ristović

.

.

.

O the great God of Theory, he’s just a pencil stub, a chewed stub with a worn eraser at the end of a huge scribble.