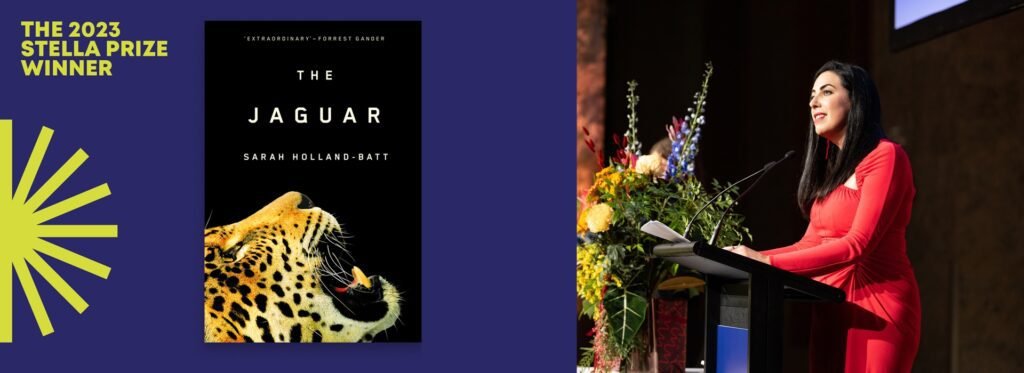

Círculo de Poesía celebra que la poeta australiana Sarah Holland-Batt ha merecido el Stella Prize 2023 por su libro The Jaguar. El jurado lo describió como: “un libro profundamente conmovedor y, con un tono final de esperanza”, destacando la poderosa forma en que “investiga el cuerpo como un sitio tanto de placer como de fragilidad”. Presentamos aquí algunos poemas del libro, con la traducción y nota del poeta Mario Licón.

The Jaguar (UQP 2022) es el más reciente libro de poesía de Holland-Batt dedicado integralmente a la memoria de su padre, que por muchos años padeció de Parkinson, el libro es una especie de bitácora de esos largos años de sufrimiento y de una peculiar relación padre-hija descrita con un lirismo atrevido e intenso, una voz diáfana y directa y un poderoso manejo del lenguaje.

Mario Licón

El regalo

Mi padre está en el jardín en su silla de ruedas

adornado con hibiscos del verano

como un santo en una estampa del siglo diecisiete.

Una guirnalda floreciente zumba alrededor de su cabeza

rojo apasionado. Él sostiene el regalo de la muerte

en su regazo: pequeño, oblongo, envuelto en negro.

Ha estado esperando diecisiete años para abrirlo

y está impaciente. Cuando le pregunto cómo está

mi padre llora. Su llanto llega como una visitación,

el cuerpo extrayendo tiernamente lágrimas de sus vasos

como una enfermera contando gotas de calamina

de una botella ámbar, como un adolescente en el lavado de carros

exprimiendo espuma de una gamuza. Es una especie de milagro

ver a mi padre derramando lágrimas así tan libremente, derramando lágrimas

por lo que se le debe. ¿Cómo estás? Le pregunto de nuevo

porque su respuesta depende del microclima de un instante,

sus estados de ánimo florecen y se retiran como una anémona

mientras las corrientes frías giran alrededor suyo

llorando un minuto, sereno el siguiente.

Pero este día mi padre está desconsolado.

Estoy teniendo un mal día, dice, y vuelve a intentar.

Estoy teniendo un mal año. Estoy teniendo una mala década.

Me detesto por notar su poesía —el triplete

que no debería ser hermoso para mis oídos

pero lo es. Día, año, década —escala de terrible economía.

Quiero darle su regalo pero no es mío

para darlo. Estamos sentados como madre e hijo en la noche de navidad

esperando a que llegue la medianoche, anticipando

el momento en que juntos podamos abrir su regalo

primero mi padre llevándolo hasta su oído y sacudiéndolo,

luego yo ayudándole a quitarle el papel,

el peso de su muerte tocando

y una vez que la caja esté desenvuelta será mía,

cargaré el regalo de su muerte interminablemente,

cada día sabré que se abre en mí.

The gift

In the garden, my father sits in his wheelchair

garlanded by summer hibiscus

like a saint in a seventeenth-century cartouche.

A flowering wreath buzzes around his head—

passionate red. He holds the gift of death

in his lap: small, oblong, wrapped in black.

He has been waiting seventeen years to open it

and is impatient. When I ask how he is

my father cries. His crying comes as a visitation,

the body squeezing tears from his ducts tenderly

as a nurse measuring drops of calamine

from an amber bottle, as a teen at the carwash

wringing a chamois of suds. It is a kind of miracle

to see my father weeping this freely, weeping

for what is owed him. How are you? I ask again

because his answer depends on an instant’s microclimate,

his moods bloom and retreat like an anemone

as the cold currents whirl around him—

crying one minute, sedate the next.

But today my father is disconsolate.

I’m having a bad day, he says, and tries again.

I’m having a bad year. I’m having a bad decade.

I hate myself for noticing his poetry—the triplet

that should not be beautiful to my ear

but is. Day, year, decade—scale of awful economy.

want to give him his present but it is not mine

to give. We sit as if mother and son on Christmas Eve

waiting for midnight to tick over, anticipating

the moment we can open his present together—

first my father holding it up to his ear and shaking it,

then me helping him peal back the paper,

the weight of his death knocking

and once the box is unwrapped it will be mine,

I will carry the gift of his death endlessly,

every day I will know it opening in me.

Nessun Dorma

Cuando veo por primera vez el cuerpo de mi padre

es apenas después de medianoche, su rostro bañado

en muda luminiscencia, una desolada sábana blanca

tirada rígidamente hasta su cuello—y recuerdo

como hacia el final de su vida

todo lo que mi padre quería era ver a Pavarotti,

su rostro malva en la luz lunar de su laptop,

repitiendo un concierto en LA en 1994 una y otra vez.

Al principio los tensos coros murmurando nessum dorma,

nessum dorma, luego entran las vibrantes cuerdas,

Il Principe ignoto, Calaf —ceño lívido,

cabello encrespado por el sudor, ojos cafés

como los de un sabueso —abre su garganta, alcanzando el trino alveolar

en dorma como un redoble de tambor, truenos, cuero, coñac,

tabaco, regaliz, anís, la oscura riqueza emergiendo,

la apertura de su boca no es bastante amplia

para el sonido que brota, la cabeza de mi padre gira

como un girasol para absorberlo todo,

los aldeanos insomnes bajo amenaza de ejecución,

buscando un nombre al amanecer, los jardines nocturnos

erizados de lirios, áster, flor de luna, jazmín

la cámara acercándose al rostro de Pavarotti,

sus hombros duros como el hormigón, la insensible Turandót

arriba en su fría recámara, estrellas como puntas de cuchillos

encima de ella, y Calaf ardiendo en su secreto,

ma il mio mistero è chiuso in me, Pavarotti cantando

ahora desde abajo de su frente, su barbilla hundida

como la de un buzo. Sólo sus cejas como acentos,

tenuto, marcato, moviéndose, el coro ligero como neblina

a la deriva en —debemos morir, debemos morir—

el pozo de la boca de Pavarotti profundizándose,

su cabeza tirada hacia atrás

por la fuerza de su voz —crisol de metal virgen,

derrame ardiente— tramontate, stelle,

y después de alcanzar la cuarta octava culminante,

el heroico Si, y el La sostenido,

reclina su cabeza y cierra los ojos,

la boca muy abierta y extasiada, como la boca de mi padre

estaba abierta cuando murió, sabiendo que la actuación

había terminado, esperando la tenue lluvia de aplausos.

Nessun Dorma

When I first see my father’s body

it is just after midnight, his face bathed

in mute fluorescence, a stark white sheet

pulled tight to his neck—and I remember

How towards the end of his life

all my father wanted was to watch Pavarotti,

his face lilac in the laptop’s moonlight,

looping a concert in LA in 1994 over and over.

First the uneasy chorus whispering nessum dorma,

nessum dorma, then the bright strings entering,

il principe ignoto Calaf—brows livid,

Hair corkscrewing with sweat, eyes brown

as a hound’s—opens his throat, hitting the alveolar trill

on dorma like a drumroll, thunder, leather, cognac,

tobacco, liquorice, anise, the dark richness surging,

his mouth’s aperture not wide enough

for the sound rolling out, my father’s head craning

like a sunflower to absorb its fullness,

the villagers sleepless under threat of execution,

hunting for a name by dawn, the night gardens bristling

with lilies, aster, moonflower, jasmine—

the camera panning in on Pavarotti’s face,

his shoulders thick as concrete, unfeeling Turandot

up on her cold bedroom, stars like knife-tips

above her, and Calaf burning with his secret,

ma il mio mistero è chiuso in me, Pavarotti singing

from under his brow now. His chin tucked

like a diver’s, only his eyebrows like accents,

tenuto, marcato, moving, the chorus light as mist

drifting in—we must die, we must die—

the well of Pavarotti’s mouth deepening,

his head tugged back by the force

of his voice—crucible of virgin metal,

burning pour—tramontate, stelle,

and after he reaches the climactic fourth octave,

the heroic B and the sustained A,

he lets his head loll back and closes his eyes,

mouth agape and ecstatic as my father’s mouth

was open when he died, knowing the performance

was over, waiting for the faint rain of applause.

El Jaguar

Brillaba como un insecto en el sendero:

esmeralda iridiscente, escarabajo navideño fuera de temporada.

Puntos metálicos en la pintura como residuos del lecho de un río,

rechinantes asientos de piel de cierva. Verde botella, lo llamaba mi padre,

o también bosque. Un tormento que trajo sin antes probarlo,

vintage 1980 XJ. Una insurrección contra su tembladera.

El único postor, ganó la subasta sin esfuerzo

al siguiente día que el doctor le dijo que pintara una raya

a sus años de manejo. Mi madre no habló

durante semanas. Resplandecía en el sendero terracota,

un gato salvaje saltando eternamente en el cofre,

depredador, el cromo deteriorándose bajo el sol,

ornamento de la locura de mi padre,

impecable y milagrosa, hasta que empezó a juguetear,

pintó los asientos de piel con acrílico

así que se descascararon y agrietaron, levantó la palanca de cambios,

hizo un hoyo en el tablero con una navaja Stanley,

bajó el asiento del conductor tan bajo

que tú no podías ver por encima del tablero. Durante meses

lo manejó aunque mi madre le suplicara,

lo manejó como si estuviera castigándola,

peligrosamente rápido en los callejones,

luego aceleraba en la autopista, a toda

velocidad, aunque se estaba quedando ciego de un ojo,

aunque mi madre y yo rehusáramos subirnos,

y por primera vez en años mi padre

estaba feliz —estaba feliz de estar manejando,

él estaba feliz de que mi madre y yo

estuviéramos sufriendo. Finalmente sus arreglos

lo destruyeron, el carro que siempre quiso y espero

por tanto tiempo para comprar, ahí estaba como un cadáver

en la cochera, como una lápida, como un ataúd

pero no es símbolo ni metáfora. No puedo ganar nada de esto.

The Jaguar

It shone like an insect in the driveway:

iridescent emerald, out-of-season Christmas beetle.

Metallic flecks in the paint like riverbed tailings,

squeaking doeskin seats. Bottle green, my father called it.

or else forest. A folly he brought without test-driving,

vintage 1980 XJ, a rebellion against his tremor.

The sole bidder, he won the auction without trying

the day after the doctor told him to draw a line

under his driving years. My mother didn’t speak

for weeks. It gleamed on the terracotta drive,

wildcat forever lunging on the hood,

predatory, the chrome snagging in the sun,

ornament of my father’s madness,

miraculous and sleek, until he started to tinker,

painted the leather seats with acrylic

so they peeled and cracked, jacked the gearstick,

hacked a hole into the dash with a Stanley knife,

jury-rigged the driver’s seat so it sat so low

you couldn’t see over the dash. For months

he drove it even though my mother begged,

he drove it as though he was punishing her,

dangerously fast on the back roads, then

opened up the engine on the highway, full

throttle, even though he was going blind in one eye,

even though my mother and I refused to get in,

and for the first time in years my father

was happy––he was happy to be driving,

he was happy my mother and I

were miserable. Finally his modifications

killed it, the car he always wanted and waited

so long to buy, and it sat like a carcass

in the garage, like a headstone, like a coffin––

but it’s no symbol or metaphor. I can’t make anything of it.